They say that there are two kinds of preachers in the world: those who have something to say, and those who have to say something. I’ve heard a lot of the latter kind of preacher, but I always tried to be someone who has something to say. Now it’s time to find a new place to share what I have to say with those who want to hear it, starting with something that’s not always easy to talk about: shame.

Shame is like a weed that puts down roots anywhere it can, often in those places where nothing else can grow. Like a weed, shame can choke out other things that might have grown in its place: something that might have been beautiful and good. But shame keeps such growth in check, crowding out anything that might have brought dignity to its place.

Shame has featured prominently in a lot of religion. In the Christian religion, people like to blame St. Paul or St. Augustine for the prevalence of shame in Christian theology. I can’t say. I’m not a theologian; I’m a preacher. I can say that as a gay man in the church, I managed to keep shame largely at bay, mostly by careful compartmentalizing. Gay people face the possibility of shame as soon as they begin to realize that there is something different about them. Teasing and mockery around gay-ness starts early for boys, and it never stops - either you learn to cope with it or you suffer.

When we find that the potential for shame is rooted in the people to whom we are attracted sexually, it’s bad enough. But then, when we realize that the possibility of shame emerges because of the people we fall in love with, it gets even worse. I used to think that the extravagant camp of gay culture was over-compensation for all kinds of things that I didn’t really understand. But now I see that, more likely, the camp is at least partly an effort to counterbalance the ever-present threat of shame - even the threat of being ashamed of who you love. Joy is a powerful answer to shame!

Gay people are not the only ones who face the possibility of shame - it’s just the shame that I know the best. Many cultures are adept at identifying classes of people as objects of shame. And many individuals have become expert at adopting their own shame for reasons bound up in no structures beyond the ones nearest to them, or maybe only within their own selves. Like a weed, shame doesn’t need a perfect environment; shame will find a way.

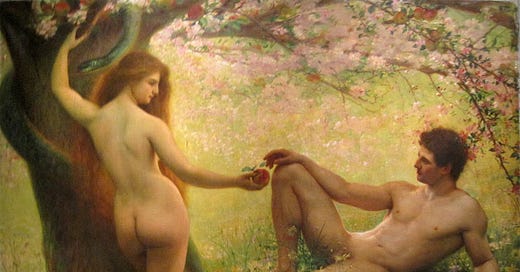

The story of the Fall (Adam and Eve’s transgression in the Garden of Eden) is closely associated with shame, and is often read in such a way that suggests a possible explanation for the origins of shame. Ending, as it does, with the first couple’s expulsion from the Garden, it clearly tells of something that went wrong. But when we read the story and conclude that God intends for us to carry a legacy of shame around with us through all ages of history, and in every human heart, that just sounds too cynical for me. I can’t see how such a conclusion could express the desire of the heart of the God of love. For years I have tried to argue forcefully against this kind of conclusion, and to search more diligently for the truth of the God’s love.

At various points in my life I have come into close proximity with the possibility that I should be ashamed of who I am. As I say, such brushes with shame are standard issue for gay people, and certainly not rare for anyone else. Since most contemporary religion has had no idea of how to handle the implications of the sexual revolution that’s taken place in the last 75 years, the situation has been ripe for trouble. Many people have dealt with it by doubling down - either in the avoidance of religion, on the one hand, or in adopting a hyper-conservative sexual ethic, on the other. These trends haven’t gotten us very far, but they have provided some fertile ground for shame.

Certainly, humans are capable of doing things to ourselves and to one another for which a reasonable response might be a measure of shame. It’s a matter of some maturity to be able to identify shame in our lives when it’s a signal that we have some important reconciling work to do. John Henry Newman called the conscience the “aboriginal vicar of Christ;” and we should examine our consciences carefully when confronting shame. We should also not be surprised to find that Christ’s response to such examination will primarily bring mercy, forgiveness, grace, healing, and love rather than accusation, denunciation, and condemnation.

Not long ago, I found myself prone to hanging my head in shame, literally and figuratively. Having either carried shame with me secretly for most of my life, or occasionally having fought it off successfully, I thought I was a strong warrior in the battle against shame; but I was a lot weaker than I realized, facing a weed that never tires of growing. Revisiting some of my own preaching helped me find a way out of the encroaching onslaught of shame. Since I always said that I never preached a sermon that I wasn’t preaching to myself, it was not hard to re-engage this way.

I remembered a sermon I preached several years ago about the shame that Adam and Eve expressed when God asked them who told them they were naked. For the first time in my life, I read that question differently - with the emphasis on the word “naked” - and a new way of reading the story was opened up for me. What if, in his encounter of Adam and Eve covering themselves up for shame, God is heart-broken to discover that the first humans were ashamed at the way God made them, ashamed of their nakedness - which was the way he intended them to be? And what if God had wanted to protect Adam and Eve from the possibility of shame? What if it’s because God is love that he had to allow for the possibility that Adam and Eve would be led astray?

Weeds can be pulled out. Although we recall one time that Jesus told his disciples to let the weeds grow alongside the wheat, more often than not, it’s better to pull out the weeds and make room for something good and beautiful to grow. I’m borrowing the title of that old sermon to define this new space where I want to share the things I have to say, in hopes that they’ll be helpful to you. I intend to reach back into my archive of more than twenty years of preaching, to remind myself and you about the messages that have held up well. And I’ll do my best to articulate new massages too, when I feel I have something to say about peace, grace, forgiveness, and love.

The full text of the sermon can be found below.

Leafless

It may be that the second most important question in all of holy scripture is asked in the few verses of the Book of Genesis we heard read just a few minutes ago. The most important question in the scriptures is asked by Pontus Pilate, when Jesus is on trial before him, and Pilate asks, “What is truth?”

But the scene of the second most important question in the Bible is familiar: the Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve hear the sound of God walking in the garden. The couple has only recently completed their first sewing project together: loincloths made of fig leaves to cover their nakedness. The crafty serpent has duped Eve, and she has shared the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil with Adam. They have discerned that an encounter with God will not go well for them, from this point on. The first question we hear in the garden is poignant, but not in the top-two questions of scripture: “Where are you?” the Lord God calls out to Adam.

Adam replies, “I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.”

And now comes what may be the second most important question in all of the scriptures, when God asks this: “Who told you that you were naked?”

Who told you that you were naked?

Now, how you ask a question matters. And how you read the scriptures matters. And how you read the way that God asks this question matters, too. I, for one, have nearly always read this question the same way, with the emphasis on the verb: Who told you that you were naked? To me, this way of reading the question has made sense. It turns the scene into an interrogation, and the emphasis is on the act of deception, establishing what went wrong in Paradise. When you read the question this way, you can hear, can’t you, that God is annoyed that the serpent has told Adam and Eve something that the two humans are not supposed to know. The problem being that what the serpent has told the couple appears manifestly to be true: they are naked. OK.

But there is at least another way of reading the question: if you put the emphasis on the subject: Who told you that you were naked? Reading the question this way tends to emphasize the culpability of the serpent, and effectively underscores the matter of blame, and where it should lie: that is, with the who in question. The difference between the two readings may be subtle, but I think it could matter.

There is, however, also at least a third way of reading this question. And I have to admit, that it had never really occurred to me before. But when you read the question in this third new way, the entire question takes on a whole new significance. You can read this question on God’s lips, with the emphasis on the adjective that is the crucial part of the clause that forms the direct object of the question: Who told you that you were naked?

By now, I expect you are asking yourself, What’s with all the grammar? So let’s leave the grammar aside for a moment and skip over to vocabulary, and particularly to this word, naked.

The indispensable, long-version of the Oxford English Dictionary, once again comes to hand.

“Naked: unclothed, having no clothing upon the body, stripped to the skin, nude.” This seems obvious, and maybe bordering on inappropriate for the pulpit. But the entry in the OED goes on a great deal longer. And when you continue reading, you start to get a picture of the depth and breadth of meaning of this word.

Naked, the OED, tells us, is often used “in comparison,” in phrases such as, “naked as a...” jaybird, although the OED does not actually provide that well-known phrase. The dictionary then goes on to describe all kinds of nakedness, and the implications of nakedness.

“Of a horse: unharnessed, or unsaddled.”

“Of parts of the body: not covered or protected by clothing, bare, exposed.”

Naked means “bare or destitute of means.”

You can be considered naked if you are “without weapons or armor, unarmed.”

If you are naked you are “without defense or protection: defenseless, unprotected.”

Even a sword can be naked - “unprotected by its sheath.”

Naked means “bare, destitute, or devoid of something.”

“Bare, lacking, or defective in some respect.”

The landscape is naked is it is “devoid of trees or other vegetation; bare, barren, waste.”

Naked means “bare of leaves or foliage; leafless.”

“Of ground, rock, etc; devoid of any covering or overlaying matter, exposed.”

A boat without sails is naked.

A floor with carpets is naked too.

“Uncovered, unprotected, exposed.”

“Seeds not enclosed in a covering” are naked.

“Stalks destitute of leaves.”

Snails without shells are naked, and so is an idea unsupported by proof or evidence.

According to the dictionary, the naked eye, as you know, cannot see as far as the assisted eye.

In paragraph after paragraph, definition after definition, to be naked is to be weak, defenseless, exposed, lesser, vulnerable, and embarrassing. Ironically, the only really positive connotation we associate with nakedness is when the truth is naked. But faced with the naked truth, someone has usually been put in a compromising or unwelcome position. Otherwise naked means bare, barren, stripped, destitute, exposed, deficient, devoid, lacking, unprotected, waste, defenseless, leafless. Every single one of these definitions of naked is a negative, a deficit, a problem.

And God comes walking through Paradise to find the creatures he has formed with his own hand, and given life with his own breath, and they tell him that they hid, because they were naked.

Who told you that you were naked? God asks.

Who told you that you were bare, barren, stripped, destitute, exposed, deficient, devoid, lacking, unprotected, waste, defenseless, leafless? Who told you to think so little of yourself? Who told you that you were less than you are supposed to be? Who told you that you are anything other than beautiful? Who told you that you bear any image or likeness that does not reflect my own image and likeness? Who told you that you are not marvelously made? Who told you that the sun does not glisten gorgeously in your eyes, and that even when you sweat you don’t look marvelous? Who told you that there is anything wrong with the way the hair falls down on your shoulders? Who told you your armpits are an embarrassment, and your feet would look better with shoes on? Who told you your cheeks are not adorable? And who told you that you’d look better with leaves on than you look leafless? Who told you that you were naked?

Just a little while ago, God had taken the rib from Adam’s side, and formed Eve from it. Adam had rejoiced and said, “this at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.” Paradise was still boundless for Adam and Eve.

The writer of this part of Genesis, inspired though he may have been, had never known a time when he had not known all about nakedness, and the shame that comes with it. So he reports to us what is to him this strange non-sequitur, that indeed, Adam and Eve had been naked, and they were not ashamed. Even to the writer of God’s sacred story, this is a conundrum, since he knows what it means to be naked. Ever since the word has been used, it has been used to shame and insult and belittle; the serpent was crafty, after all. Perhaps his greatest craftiness was in convincing Adam and Eve that they had something to be ashamed of, in and of themselves. The best the biblical writer can do is tell us that they were naked, but not ashamed. This is a condition he can’t quite make sense of, but it was true. So he lets it just hang there, as if to say, “You figure it out.”

But to God, for whom this man and this woman are the pinnacle of his creation, who loves every curve of their flesh, and who delights in the mechanics of their thumbs, and the intricate eco-system in their guts, and in the bonus of pleasure that he provided to their reproductive systems, and who determined every fold of their grey matter in their skulls, and who shaped the arches of their feet, and who tuned the inner workings of their vocal chords... to God it must be a moment of severe and heart-wrenching grief at the realization that the perfection of his creation has been spoiled so quickly and damaged so deeply. Who told you, my dear children, that you were naked?

An old friend of this parish, now gone to God, Fr. Julius Jackson, used to say to his prison congregation at Graterford Maximum Security Prison, not far from here, where I had the privilege of visiting once or twice; he used to say, “know who you are, and let the rest of the world figure it out.” Fr. Jackson was quick to point out that the world prefers things the other way: the world wants to tell you who you are, and then make you figure it out. This was Julius’s summary of the Gospel to those who had been sentenced to dwell for year after year in the confines of their shame, their rebuke, their deficiency, their offense.

But Julius knew that those men in that prison need desperately to know who they really are, which is to say that they are children of the God of love, for whom he sent his Son to save them from their sins, just like the rest of us. The rest of the world had long ago decided that they were naked, so to speak: that they are bare, barren, stripped, destitute, exposed, deficient, devoid, lacking, unprotected, waste, defenseless, leafless - and that’s putting it kindly for a bunch of men in orange prison coveralls. But Julius knew that every single one of those prisoners is a creature whom God has formed with his own hand, and a beloved child to whom God has given life with his own breath.

That’s just accounting for the prisoners. How many other categories, groups, and individuals on this earth have been made to feel by some beguiling tongue that they are bare, barren, stripped, destitute, exposed, deficient, devoid, lacking, unprotected, waste, defenseless, leafless? Why else do we need a #MeToo movement? Why else do we need a Pride parade? Why else do we need an Anti-Defamation League, and an NAACP?

Who told you that he could have his way with you just because he is a man? Who told you that you are a sissy, and an abomination in the sight of the Lord? Who told you that you should be shut up into ghettoes, rounded up and exterminated? Who told you that you should be slaves; and then gave you a moniker so disgusting and demeaning that most decent people will no longer even allow that word to cross their lips? Who told you that you were naked?

Who told you that you were bare, barren, stripped, destitute, exposed, deficient, devoid, lacking, unprotected, waste, defenseless, leafless? Who told you to think so little of yourself? Who told you that you were less than you are supposed to be? Who told you that you are anything other than beautiful? Who told you that you bear any image or likeness that does not reflect the image and likeness of God? Who told you that you are not marvelously made? Who told you that the sun does not glisten gorgeously in your eyes, and that even when you sweat you don’t look marvelous? Who told you that there is anything wrong with your hair? Who told you your armpits are an embarrassment, and your feet look better with shoes on? Who told you your cheeks are not adorable? And who told you that you look better with leaves on than you look leafless? Who told you that you were naked?

Once, when you really were leafless, naked as a jaybird, God came looking for you, so that he could gaze for a while on the crowning glory of his creation. Maybe he was looking for you so he could tell you how beautiful you are.

And when he found you, you were hiding from him. Which was inexplicable to him. And he called out to you. And when you answered, you broke his heart, when you said that you heard him coming and you were afraid because you were naked, and you hid.

And with tears welling up in his eyes, because he surely already knew the answer to the question, (God knew exactly who it was that we’d been talking to), God asks that awful question that foreshadows so much of the rest of human history, “Who told you that you were naked?”

And the rest is history.

Preached on 10 June 2018

Saint Mark’s Church, Philadelphia

This was the single most moving sermon I've ever heard, and the many people I have shared it with since have said as much. Very glad to see you taking it as a touchstone!

Your words and your persona is so greatly missed in our community.........whomever the cause or whatever the reason for your not being among us, brings much sadness. But thank you for Leaf-less (I now get the title) keep writing, keep preaching and absolutely keep expressing the void that now encompasses us.