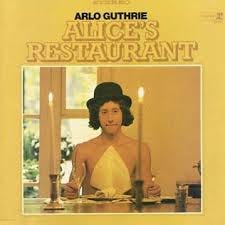

Everyone should memorize the chorus of the great Arlo Guthrie song “Alice’s Restaurant” early in life, just in case you ever need to sing it. My father had a copy of the vinyl LP that he played every year around this time - often enough, at least, that the tune and the words of the chorus were internalized by us Mullens. And at various times in my life, not infrequently, it has seemed like a good idea to have another listen to “Alice’s Restaurant.” A pub-owner in Ireland, who became a friend of mine over the years, once quieted everyone in his small pub so we could stop and listen to all eighteen minutes of the song; it was magical.

I listened to “Alice’s Restaurant” again the other night, and I was surprised to discover that doing so has become more than an opportunity for nostalgia; it has become an occasion for reflection and discovery. There is more to “Alice’s Restaurant” than meets the eye.

Remember that the song recounts the tale of a Thanksgiving feast and the offer of the guests at that feast to dispose of the trash that had been accumulating at Alice’s home (not her restaurant). Recall that “Alice doesn't live in the restaurant, she lives in the

church nearby the restaurant, in the bell-tower, with her husband Ray and

Fasha the dog.” In fact, that church, in Great Barrington, MA, which now houses the Guthrie Center, was an Episcopal Church, built in 1829 as St. James Chapel, and enlarged in 1866, when it became Trinity Church. It was deconsecrated and sold to Alice and her husband 98 years later.

At the outset, the song seems to be a tale of no-good-deed-going-unpunished. After Thanksgiving dinner, Arlo and his friends find themselves locked up in jail for littering, because they had not disposed of the trash properly. The first part of the song is a protracted reflection on the ability of a system to grossly over-react to a transgression that lacks either malicious intent or an identifiable victim. Let me tell you that there are people in this world with whom such a story resonates.

“But,” says Arlo, “that’s not what I came to tell you about. Came to talk about the draft.” And the second half of the song is a war protest song, that takes place at the draft office, where, after the discovery of his arrest record, Guthrie is sent to sit on “the bench that says Group W.” He tells us that “Group W's where they put you if you may not be moral enough to join the army after committing your special crime. And there was all kinds of mean nasty ugly looking people on the bench there.” Arlo initially feels out of place on the Group W bench, as a mere litterbug among such vicious company, but when he clarifies that he was also accused of “creating a nuisance” the fellowship of kindred spirit is established, as they compare notes on their crimes and talk about “all kinds of groovy things.” Let me tell you that there are people in this world who can identify with being sent to sit on the Group W Bench for littering… and creating a nuisance.

Eventually, Arlo confronts the sergeant in the room, saying, “I mean I'm sittin’ here on the Group W bench 'cause you want to know if I'm moral enough to join the army, burn women, kids, houses and villages, after bein' a litterbug.”

The sergeant replies, "Kid, we don't like your kind, and we're gonna send your fingerprints off to Washington." Let me tell you that there are people in the world who can identify with this interaction, too, who know what it feels like to to be told, “we don’t like your kind, and we’re going to keep an eye on you.”

In its entirety, “Alice’s Restaurant” suggests that the center of gravity of our moral universe may be out of kilter. This conclusion remains a reasonable one to reach fifty-seven years after the song was first performed.

As a literary expression “Alice’s Restaurant” leans heavily on nonsense, especially in the recurring chorus (in four-part harmony), which seems to be saying something, but of course means nothing much. Such nonsense reflects back to society the nonsense of imprisoning would-be do-gooders for littering. More poignantly, it mirrors back the nonsense of war, and of designing a complex system of determining whether or not you are “moral enough to join the army after committing your special crime.”

The conflict presented in the song is that Arlo and his companions regularly find themselves outside some ill-defined boundary of legitimacy: they did not dispose of litter properly, and Arlo’s arrest record for littering marks him as unfit for the violence of warfare. These are both absurd conclusions that are probably answering absurd questions. And so the song presents us with an absurdity to sing in the well-known chorus: “You can get anything you want at Alice’s Restaurant…”

As the song begins to wrap up, Guthrie aligns himself with my mission of encouragement, as he tries to explain: “the only reason I'm singing you this song now is ‘cause you may know somebody in a similar situation, or you may be in a similar situation, and if you’re in a situation like that there's only one thing you can do and that's walk into the shrink wherever you are, just walk in say ‘Shrink, You can get anything you want, at Alice's restaurant.’” Then he imagines fifty people coming together to sing this anthem of absurdity. “Can you imagine fifty people a day, I said

fifty people a day walking in singin’ a bar of Alice's Restaurant and walking out. And friends, they may think it's a movement! And that's what it is, the Alice's Restaurant Anti-Massacree Movement, and all you got to do to join is sing it the next time it comes around on the guitar.”

The point of such movement is to see the absurdity of grossly over-reacting to minor transgressions that lack malicious intent or victims. The point of such a movement is to see the absurdity of evaluating one’s moral suitability to wage the violence of war. The point of such a movement is to speak nonsense back to nonsense in order to be clear that you will not willingly comply with the nonsense. You choose benign nonsense over destructive nonsense in a world in which nonsense seems to be inevitable. And, as Guthrie says in the song, “if you want to end war and stuff you got to sing loud.”

Listening to “Alice’s Restaurant” on Thanksgiving, however, puts the nonsense in the context of the insistence that we have much for which to give thanks, and it’s this context that elevates Arlo Guthrie’s great work above an expression of nihilism. In the course of the narrative Alice provides not one, but two Thanksgiving dinners “that couldn’t be beat.” The blessings presented in the song include not only Thanksgiving feasts, but also deep relationships that weave the cast of characters together.

It has been deeply unsettling to find myself sent to sit on the Group W bench after twenty-eight years of what I think you could call fruitful service to the church. I can’t begin to make sense of the nonsense in this world of ours. But I know that I have much to be thankful for. That reality has never been unclear to me. And all that I have to be thankful for has been highlighted again this Thanksgiving as I’ve enjoyed feasts with family and friends, and as I have been reminded of the deep relationships with so many wonderful people with whom my life is woven and intertwined.

You can get anything you want at Alice’s Restaurant.

“Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” was written by Arlo Guthrie, and released by Warner Brothers in October 1967.

"...the center of gravity of our moral universe may be out of kilter." Thank you, Your Magnificence.

Sitting W, being redeemed, avoiding massacres